Home » Posts tagged 'Harold Lloyd'

Tag Archives: Harold Lloyd

If Ghostbusters Was Filmed In The 1920s…

In between graduate school and my 80-year-old grandmother moving in with my family, things have been rather insane as of late. That being said, I’m not going to forget my duties as a historian and recast a modern comedy film for the Great Silent Recasting Blogathon!

Deciding on a film was the most difficult part. I had some ideas for a silent It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, but that film was released in late 1963 and therefore just misses the 1965 cut. I sat down and thought about my favorite post-1965 comedy films and then remembered that for Halloween I’d actually drawn a Comedian Heaven picture with four comedians who’d actually all appeared in silents – and all for Hal Roach Studios at one point.

This is what I drew:

Ignore the bad visual pun of Buster Keaton as a ghost in the background.

Ignore the bad visual pun of Buster Keaton as a ghost in the background.

The whole thing started because one day I realized that Harold Lloyd would have made an absolutely perfect Dr. Egon Spengler. It ended up expanding when I remembered that upon the arrival of the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man Ray actually says, “I couldn’t help it,” a line often squeaked out by a Mr. Stan Laurel in moments of desperation. Since Stan and Ollie have to stay together at all costs, Ollie filled in as Venkman, and Charley Chase rounded out the group as latecomer Winston Zeddemore.

Were such a film to actually be made at Hal Roach Studios during the silent era, it would have to be after 1927 to have Stan and Ollie officially teamed up as Laurel and Hardy but before 1929, when the studio converted to sound productions. Harold Lloyd would also have to be coaxed back to work with producer Hal Roach one last time, as he’d moved on and was working independently by the late 1920s. Leo McCarey would be present to direct, so he wouldn’t have to be dragged back from anywhere.

To round out the cast, we need a couple of love interests, a villain, and an antagonist or two. Dana Barrett, Venkman’s love interest, would probably be played well by Thelma Todd, who was alternating between Paramount and First National in the late 1920s but was at Hal Roach Studios by 1929, as she appears in Unaccustomed As We Are with Stan and Ollie (their first talking film). Thelma’s certainly adept at playing comedic romantic leads (as her work with the Marx Brothers shows), so we’ll have her play Dana. For Janine Melnitz, the Ghostbusters’ secretary who eventually ends up dating Egon, I thought it would be particularly cute to bring Harold Lloyd’s real-life wife Mildred Davis out of retirement (she briefly did return to the screen in 1927) and have her fill the role because Harold, as mentioned above, is the perfect Egon.

With those two cast, we need to find someone to play Dana’s awkward neighbor Louis Tully. Considering Rick Moranis’s small size, Charlie Hall might be a nice fit height-wise. For the opposing forces, antagonistic lawyer Walter Peck would be played to perfection by Edgar Kennedy, the mayor could be played by the great James Finlayson just because the idea of Fin as the mayor of New York is hilarious, and Gozer’s physical form could be portrayed by – who else? – Mae Busch.

It could work, I suppose, if those nuclear streams used technology that was available at the time – special magnets, for example, or perhaps vacuums. What’s more important is trying to figure out how Hal Roach Studios could pull off the Stay Puft Marshmallow Man.

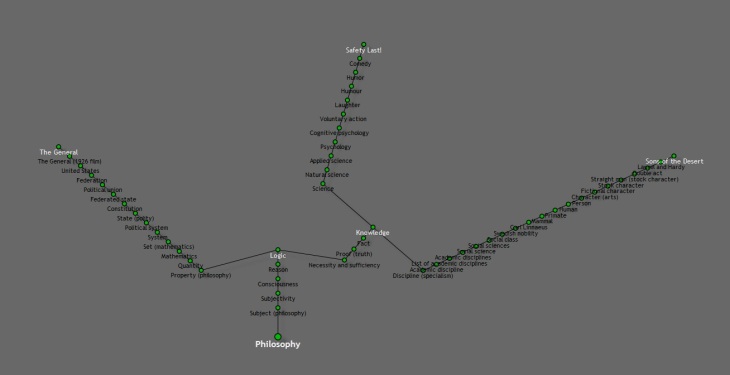

Xefer On Comedy

Xefer is a fun little website where you can see how many clicks it takes you to get from any random Wikipedia article title to the philosophy article. Basically, it’s the world’s greatest time-waster not called Tumblr. I decided to play with it by typing in three different comedy films and seeing what it came up with. I used, in order:

- Sons of the Desert (1933, Laurel and Hardy)

- The General (1926, Buster Keaton)

- Safety Last! (1923, Harold Lloyd)

And here’s what happened:

I think my favorite part was how ‘Sons of the Desert’ somehow went through the ‘Carl Linnaeus’ article. I don’t know why, but that just cracked me up.

Comedy Travels In Cycles

I rewatched It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World for the first time in years last night. (A large portion of the cast of that comic I’m doing appears in this thing, amongst other reasons.) Besides possibly disturbing my parents a little bit by recognizing the way Buster Keaton (who cameos) walked, I did a little bit of thinking last night – and it’s true, comedy really does travel in cycles stylistically.

When comedy films first started appearing, Mack Sennett more or less ran the show. Sennett films relied on heavy slapstick – watch anything featuring the Keystone Kops and you’ll see what I mean. Watching Sennett’s Chaplin, Arbuckle and Normand films reveals…basically the same thing. There were no scripts back then – the actors would just go out with the director and a cameraman, find a scene somewhere, and improvise a little story. They’d then add title cards later after the film was edited and cut.

Then one day, Charlie Chaplin decided to believe all the critics calling him an artist, and things changed drastically. Films became longer, with proper plots carried throughout them. There weren’t scripts, because there was still no dialogue, but by the middle of the 1920s, the Big Three – Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd – were well-established, with Harry Langdon more or less keeping up with them (until he decided he was an artist, too, but let’s not get into that now). These films moved away from slapstick and became more situational, with the characters spending most of their time on film trying to get out of bizarre – yet realistic – situations.

And then sound came.

Now, you don’t need sound to make a comedy, but when sound arrived, everyone decided that now was the time for snappy scripts and puns. There was an over-reliance on dialogue, which naturally ruined quite a few potentially good films. By the time films and moviegoers had gotten used to sound, quite a few of the great comedians of the 1920s had fallen off the wagon. (The Big Three continued to make and appear in films, but their work during this period isn’t considered their best output, and Harry Langdon did quite a few talkies, as well, but eventually joined the writing team at Hal Roach Studios.)

If we look at the sort of comedy that was popular during the 1930s, we see two or three distinct branches. The first branch, which involves scripts heavily reliant on wordplay and puns, is primarily dominated by the Marx Brothers, but there were quite a few other acts falling under this umbrella, as well. Remember Wheeler and Woolsey? No? Anyway, they were here, too.

The second branch involves a return to slapstick. Columbia decided that at the height of the Great Depression what people really wanted to see was three idiots beating each other up for twenty minutes, so they signed these three and set them to work. Apparently Columbia was right, since they turned out to be a massive draw at the box office.

The third branch – my favorite – is probably the best-remembered of the three because they seem to be involved in almost everyone’s childhoods, even now. To be fair, the thing that makes Laurel and Hardy so special to me is that the two of them ended up becoming best friends over the course of their careers, which is the most adorable thing ever. From a comedy standpoint, they’re very different from the other two branches because of their pacing. Whilst the other acts relied on quick, snappy dialogue and non-stop cartoon violence, Stan and Ollie took things very, very slowly. They reacted to what happened to them – slowly – and stretched sequences that would have taken other comedians thirty seconds to do out over several minutes. It worked brilliantly.

By the 1940s, things needed to be freshened up some, and although the Stooges and Stan and Ollie were still around, it was Abbott and Costello who popped up and grew in popularity during the war years. (This may have reflected the general culture in America at the time, as Bud and Lou’s comedy style was more aggressive.) They hung around in the ’50s for a little while, but Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis picked up the baton from there and brought comedy into more of a screwball direction. At the same time, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope’s Road To… movies were further solidifying the genre. Television comedy also began its rise, with many radio stars eventually making the jump and bringing sketch comedy and sitcoms to the small screen.

Which brings us to It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, which came out in 1963. There are elements of several styles of comedy in this movie – which makes sense, because there are several styles of comedians in it. If we take a closer look at it, we can dissect it a little bit:

- Mack Sennett would have loved this movie. There’s plenty of slapstick violence in here – the film even ends on a banana peel gag, a staple of the Sennett era. Although there isn’t a pie fight, there’s a bit where an entire gas station is systematically dismantled and destroyed by Jonathan Winters, which is close enough.

- There’s a ton of situational comedy, too. The entire movie is fueled by one situation – Jimmy Durante’s character hid money somewhere in Southern California under something called a ‘big W,’ and everyone’s attempts to get there first place them into precarious situations: hitchhiking with strangers and ‘borrowing’ their cars, flying an airplane after the pilot passes out drunk, locked in a hardware store basement, and so on.

- The script is phenomenal. It allows all the comedians making cameos to get their trademark lines in (ZaSu Pitts gets to show off her Midwestern accent as the switchboard operator, Jack Benny gets to deliver a “…Well!” and Joe E. Brown gets to scream “HEEEEEEEEY!” near the end). It also lets the feature players shine (Buddy Hackett’s delivery of “What are you, the hostess?” to Mickey Rooney as they’re trying to land a plane is my dad’s favorite line in the entire film). The script is snappy and rapid-fire where it needs to be and quiet when all the audience needs to follow the plot is the action.

- For a three-hour movie, the pacing is incredible – you never get bored because the plot never drags for a second, even when the scene cuts to the police station for a breather.

You watch this film, and cameos aside, the films of the 1910s and 1920s are back – in color and in a much longer format, but there you go. Styles of comedy tend to cycle around. In the early 1960s, there was a satire boom which started in the UK and made its way to the US. Although Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, who were at the forefront of the movement by being in Beyond the Fringe, lasted as a double act for twenty some-odd years afterwards by moving into sketch comedy, satire itself faded quickly out of vogue, only to return with a vengeance in the 2000s. My brother loves films like Dodgeball. Dodgeball is pure slapstick.

Think for a moment about what you like watching. There might just be some older – or newer – films in the ilk of what you’re into. Why don’t you go and check those out for a change and see what you think?