I Was In A Nitrate Vault This Week

I’m not liable to spontaneous combustion, but as a human being I am flammable so it was probably for my own good.

As an archivist, you get to do some pretty cool things and go to some pretty cool places in the name of preserving history, and Monday was no different – I was in an old film processing building attending the orientation for my newest adventure in my perpetual Quest For Permanent Archival Employment, some paid training at IndieCollect, an independent film repository (check them out!). As it were, the building still has five nitrate vaults in it, so naturally I had to investigate the nearest one since I’d never gotten to go inside one before.

Photos after the cut.

Quick Hit: Harpo Marx is the World’s Cutest Dad

Again, this is a very brief post since I’ve been very busy with my new library job, but someone in the Marx Brothers Council of Facebook linked to this adorable footage in the group and I had to share it. It’s Harpo with one of his sons, Bill, in 1941.

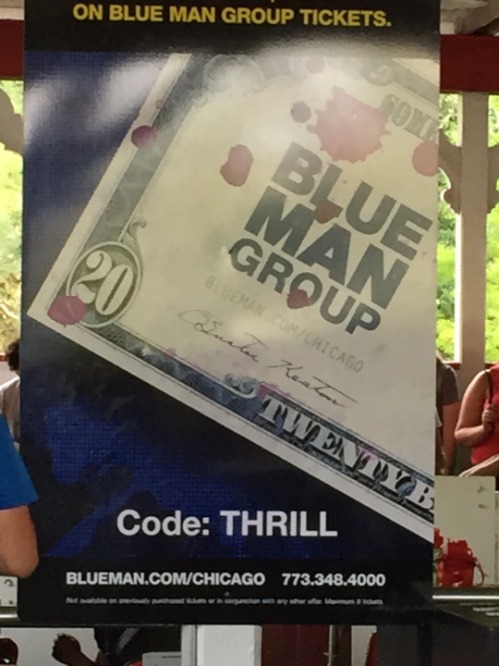

Quick Hit: Buster Keaton money?

This is just a quick hit here, but one of my friends on Tumblr sent me this image. Look at the signature on that dollar bill.

Finally, a Guide to the Marx Brothers!

Today is the publication date of Marx Brothers Council of Britain blogger Matthew Coniam’s seminal work on all the references and in-jokes in the films of the Marx Brothers. The book is being published by McFarland and can be bought directly from the publisher here!

I’ve preordered my copy on Amazon and I can’t wait for it to arrive. Although I’m a trained historian, I know far from everything and I know there are tons of references I’m missing when I watch these films, so I’m really excited to do a rewatch with the guide in hand. Sure, most people know about Strange Interlude, for example, but for every reference modern audiences still get there are at least five more we don’t!

As a member of a Marx Brothers Facebook group, I’ve seen the work that has gone into this book and I can confirm that Matthew and his team have worked tirelessly to bring us this extremely important book. I may not have my copy yet, but I’m already recommending this to you. Seriously, go buy this. If you’re a fan of the Marxes you won’t regret it.

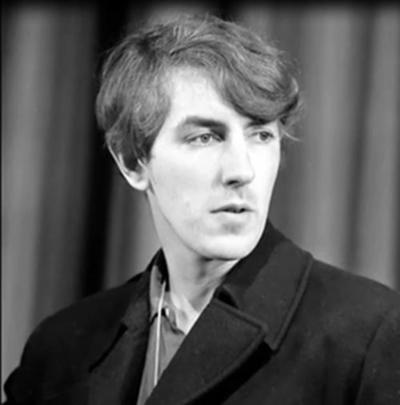

20 Years of Missing Peter Cook

It’s been twenty years today since Peter Cook left us, and a group of people from Tumblr, myself included, rewatched a lot of his material, including both sketches and the 1967 film Bedazzled, in his honor. It gave me an opportunity to reflect on how brilliant his writing actually was again and just how influential his material was for generations of comedians afterwards.

It’s been twenty years today since Peter Cook left us, and a group of people from Tumblr, myself included, rewatched a lot of his material, including both sketches and the 1967 film Bedazzled, in his honor. It gave me an opportunity to reflect on how brilliant his writing actually was again and just how influential his material was for generations of comedians afterwards.

I figured this would be a great time to reflect on it all with those people he influenced, as well as some of his compatriots, so here’s this lovely documentary someone posted on YouTube in six parts to watch and enjoy. I figure it’s better to watch funny things instead of spend the entire day crying.

Someone Finds Alan Bennett’s On The Margin, I Cry

I know there’s a certain bias towards the Oxbridge School of Comedy on this blog. It’s their fault that I ended up deciding to really academically study comedy in the first place (who even does that to begin with?), but they’re brilliant to boot and their influence on comedy is still felt long after their ascendance in the 1960s.

Unfortunately, a lot of what members of the movement did was lost due to a horrendous practice called tape-wiping. You can ask any of my archival colleagues what that is and they’ll probably all grimace or make other disgusted faces at you. We don’t like it very much nowadays, but it was often the norm when a studio needed to reuse tapes due to space and monetary concerns. Tapes of television broadcasts were cleared of data and reused over and over again, and as a result a lot of valuable material was lost. That’s why we only have a little bit of the famed Not Only…But Also, one of the major groundbreaker programs during the period. I’m still not over that. I don’t think I’ll ever be over that. Peter Cook and Dudley Moore offered to buy the tapes and pay for new ones and they still wiped it.

I’m totally not bitter or anything. Okay, yes I am.

I’m heartened now, though, because apparently back in March someone managed to uncover audio of all six episodes of Peter and Dudley’s Beyond the Fringe confederate Alan Bennett’s program On The Margin, which ran in November of 1966 and repeated twice in 1967 before allegedly being a victim of the tape-wiping epidemic:

Audio of Alan Bennett’s first major TV show has been recovered, decades after it was wiped in a bid to save tape.

The recordings of the six-part satirical BBC Two series On The Margin were made in 1966.

The show, written by and starring Bennett, also featured Prunella Scales and John Sergeant, who later became the BBC’s chief political correspondent.

The recordings, made during a 1967 repeat of the series, are due to be returned to the BBC archive.

The show, which originally went out on BBC Two, contained satirical and observational sketches, including its own mini-soap opera.

There were also serious poetry and musical slots during the programme, including readings from actress Scales, and archive footage of music hall stars.

On The Margin was a critical success, and was repeated on BBC One, prompting the wrath of television campaigner Mary Whitehouse.

She objected to a sketch which contained the line “knickers off ready when I come home” and was perceived as insulting to Norwich, which emerges by putting together the first letter of each word.,

The programme was wiped after its final broadcast, with tape recycling a common practice at the time.

Michael Brooke, writing for the British Film Institute, said the show was “one of the most notorious victims” of material being destroyed.

It was feared that with the exception of some fragments, On The Margin had been lost forever.

I’ve always held out hope that these shows would turn up in some format somewhere, and it’s a huge relief to know we haven’t lost On The Margin completely after all. It makes me believe that my beloved Not Only…But Also is out there somewhere and might just be recovered someday.

An archivist can dream, you know.

It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad Kickstarter!

Hey, you! Do you want an awesome book about an awesome movie? Of course you do!

Author and artist Dave Woodman has a Kickstarter going to publish an absolutely delightful book on It’s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, one of the greatest comedy films of all time. Check out the video below:

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1044631930/its-a-mad-mad-mad-mad-book/widget/video.html

I can’t even begin to stress how wonderful this would be, so give it a look and back the project if you love the movie! This book looks incredible, seriously.

A Trip to the Fort Lee Film Commission

For a graduate school assignment, I had to interview an archivist, and being the North Jersey resident and comedy researcher that I am, I sought out the archives at the Fort Lee Film Commission (and its Keystone collection) and had an audience with archivist Tom Meyers. The following is the ten-page piece I had to write for my grad school professor after the interview, during which I was required to gather information on a large list of archival-related topics. You can find the Fort Lee Film Commission online here, and if you ever get a chance to visit I highly recommend you do!

In 2000, the impending demolition of a home once belonging to actor Maurice Barrymore (and his three famous children, John, Ethel, and Lionel) spurred the Fort Lee Historical Society in Fort Lee, New Jersey to action. They created a movement to spare the historic house from demolition by educating the public about its history and importance, but unfortunately this small grassroots movement was not enough and the former Barrymore residence was demolished to make way for some new construction.

Fast forward thirteen years, and the much larger Fort Lee Film Commission has just successfully saved Rambo’s Saloon, a building where film crews in the area would gather for lunch and swap trade secrets over ham and eggs, by protecting it from demolition and agreeing to the building’s conversion to low and middle income housing instead. This time around, the Commission, now an official offshoot of the Fort Lee Historical Society, had enough funding and outreach ability and was able to successfully lobby the town government to protect the historic building. An online petition to save Rambo’s Saloon was signed by early film fans all over the world, one promoted by the Commission’s website and its social media outlets. What a difference a few years makes.

On Friday (12/7/13) I had an opportunity to meet with the executive director of the Fort Lee Film Commission, Tom Meyers, and I asked him a number of questions about the archives, the Commission’s mission, and the holdings the archives were comprised of. (I also made no secret of my comedy research, and he was quite willing to help me out.) My hour and a half spent in Fort Lee opened my eyes to an incredible little organization that deserves far more attention and funding than it gets.

The Fort Lee Film Commission was created by an ordinance in 2000 as a spur of the Fort Lee Historical Society due to their campaign to save the Barrymore home from demolition. Although this venture failed, the Commission continued to operate in association with the New Jersey Motion Picture and Television Commission in an effort to bring filmmaking and other media production back to the state of New Jersey and also began a movement to promote the filmmaking history in the town of Fort Lee itself. Since 2000, the Commission’s mission has been to commemorate Fort Lee’s rich movie history, preserve this history, screen films of cultural and local significance, encourage current-day filmmakers (especially high school students interested in film), and educate the general public about the history of the area. The Commission has certainly succeeded with regard to educating the public, as its bid to save Rambo’s Saloon earlier this year was far more successful than their attempt to rescue the Barrymore home. More than anything, however, the Commission works to make its collection as accessible as possible to researchers, visitors, and students, as well as anyone with an interest in film history, as they believe (correctly) that an archive is useless unless it is accessible and the information contained within can actually be used.

The Fort Lee Film Commission’s archival collection is comprised of thousands of film stills, artifacts from families living in or formerly from Fort Lee, costumes, artifacts, and props from studios, and more than a few actual preserved silent films. Although they do not have a storehouse for these films on-site, they are preserved very safely and carefully in a film storage facility also in Fort Lee, complete with what Mr. Meyers termed a “nitrate shack” to protect the films in case of fire (because nitrate film has a terrible tendency to spontaneously combust). The collection contained on-site in the Fort Lee Museum is preserved in archival boxes shelved in the office upstairs, although the Commission is planning to move to a larger facility containing a film museum and a screening theatre within the next few years that will allot for more archival space and facilities, a much-needed move as the collection is currently threatening to take over the entire office area. This new museum will hopefully be completed and opened in 2016 in a new development currently being constructed in Fort Lee.

The Fort Lee Film Commission has a very small staff – Mr. Meyers is the only paid employee, as he is a direct employee of the borough of Fort Lee as a member of the historical society. Everyone else, including all other full-time employees of the Commission, are volunteers, including high school and college students who work as interns scanning items in the collection. As a small organization, acquisitions are mostly handled by two or three of the official members of the Commission who use their spare time to help locate items, stills, and films that depict or are related to the history of Fort Lee, especially items related to its film history. The Commission is an avid user of eBay to locate and purchase (or bid on and win) these artifacts and documents, and it often seeks out private collectors and archive houses (such as the George Eastman House in Rochester) for items that it can loan, make copies of, or even buy. Oftentimes, donors find the Commission through its website and approach them first, as well.

The Commission’s biggest success in the realm of acquisition and preservation is its print of Robin Hood from 1912, the world’s only known surviving copy. An elderly gentleman from California contacted the Commission and informed them that he possessed a print of the Éclair Studios film, which was shot in Fort Lee, but had somehow run into trouble when bringing it to the UCLA Film and Television Archive for restoration and was willing to offer it to them instead. Although confused as to how the man was unable to donate the print to UCLA, the Commission accepted the print and the man sent it over by mail – a huge risk, as it was not in the best condition and could have gone ablaze at any point in its journey. Somehow, the 30-minute film arrived in Fort Lee unscathed, and the Fort Lee Film Commission set about restoring it from the safety print whilst the nitrate copy was destroyed. The restored print has since been shown at film festivals around the world, including one at the Museum of Modern Art, and is the Commission’s pride and joy.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding not much progress has been made on producing finding aids. Researchers interested in the collection can often get a general idea of what the Commission’s holdings are from clips and news blurbs posted on its website, but in order to find out exactly what the Commission is in possession of they have to make official inquiries. The Commission does know where all of their holdings are located within the offices and have internal finding aid lists, but unfortunately have been unable to create an online finding aid as of the writing of this article.

What the Commission does do, however, is utilize social media quite readily and quite well. The Commission has a Facebook presence and a Twitter account and regularly interacts with other silent film fans; this networking has actually helped them locate more items for their collection and has helped with their fundraising activities, as well. By keeping an active online – and social – presence, the Commission actually has brought in more visitors and researchers than it would have with just a static website alone. The Commission’s website is updated frequently with film clips and images from its collection, as well as with news about events, fundraisers, and its current projects. Exhibitions at the Fort Lee Museum, whose attic the Commission’s archive is located in currently, are also promoted, especially as many of these exhibitions feature items in the Commission’s collection and are curated by Commission members. This online promotion brings in new visitors – as well as returning ones – to the Fort Lee Museum, creating a highly beneficial relationship between the two related organizations. Twitter and Facebook posts help to call attention to the exhibits, as well, which brings an organization primarily focused on the film industry in the 1910s and early 1920s into the 21st century.

Perhaps the most interesting facet of the Fort Lee Film Commission is its average patron. The truth is that there is no real average patron, an oddity for such a small historical organization; in fact, the Fort Lee Film Commission is regularly contacted by researchers and film fans from all over the world. Their highly active internet outreach has extended their reach to all corners of the globe with internet service, and fans, historians, and locals frequently contact them with inquiries about the collection. Film fans marvel at the extent of the tiny Commission’s massive collection and enjoy discussing the holdings with the extremely knowledgeable staff. Fort Lee residents and other locals enjoy perusing the collection and the Fort Lee Museum in order to better understand their own history. School groups from the area often visit the museum and look at the exhibits, as well – especially important as one of the Commission’s chief missions is education. (The children who visit these days are far too young to be aware of the now-defunct Palisades Amusement Park which operated just to the south, which the museum and the Commission have a large collection on, as well, as early on the park was operated by the Schenck brothers, film producers themselves.)

Researchers, however, make up the largest group of collection users. The Commission is in regular correspondence with many of them, and these researchers range from local film buffs to serious historians from all over the country. Many of these researchers and historians even come from overseas – in one instance related to me by Mr. Meyers, a researcher from Finland contacted the Commission searching for images to use. When the Commission began its campaign to rescue Rambo’s Saloon from impending demolition, it started an online petition which was eventually signed by film fans and researchers from all over the world, and this international outpouring of support helped to rescue the historically significant building. For a very small organization, the Commission’s online presence and outreach is incredible, especially given its interaction with researchers from all over the world. Perhaps it is because silent film, with no dialogue required and easily translated intertitles, is a universal language understood the world over. Indeed, many early films have been rediscovered in archives all over the world and painstakingly restored, and the Commission is currently working to try to repatriate a film from – of all places – an archive in Warsaw, Poland.

Preserving these films and other items in the collection is not the easiest of tasks for the Commission, as they are not funded as well as they should be, but they nevertheless do their best with their available resources. The film stills and other documents are stored in archival boxes in the Fort Lee Museum’s attic, where the Commission’s offices are currently located, but will be moved to a proper archival facility in the planned film museum once construction is complete (which is estimated to be in 2016). The archival boxes are contained in fireproof containers, and many of the contained stills and documents are additionally in archival slips to further preserve them from any harm. The Commission’s film collection itself is, as mentioned earlier, stored off-site in a proper film storage facility complete with a “nitrate shack” elsewhere in Fort Lee.

Film preservation is no easy feat, especially when highly flammable nitrate film is involved. In order to preserve their films, the Commission turns to outside film restoration companies in the area to help them out and raises the funds for restoration by selling merchandise and holding fundraising events. Films are restored by copying the original nitrate prints or the safety prints to newer, less flammable film formats (often 16mm or 35mm) and then often digitally cleaning the films up. The original prints are then preserved in fireproof vaults to protect them should the nitrate combust. In the case of the Commission’s restoration of Robin Hood, the original nitrate print was in such volatile condition that it had to be safely destroyed with most of the restored content coming from the film’s safety print, although some frames were able to be rescued from the original reel. Backups, of course, are a necessity when one is working with film, and the entire collection has backup copies housed off-site in order to ensure extra preservation. In addition, the Commission is working with the Fort Lee Public Library to digitize its collection of film stills, which the library will eventually make available online. (As the Commission does not get the funding it deserves, this connection with the library allows the Commission to place much of its content online in a cost-friendly way and also improves its community outreach.)

For a collection as rare as the Fort Lee Film Commission’s is, security is of utmost importance. Fortunately, the Fort Lee Museum, where the Commission’s offices are located, is a borough building, which automatically limits outside access to the holdings and protects them from harm (and theft). The building has several alarms – one on the door to the offices and one to the main door to the building – and if an alarm is tripped the Fort Lee Police and Fire Department are notified immediately. The office also has sprinklers in case of fire, and since the entire collection has backup copies stored elsewhere if anything is damaged in a fire or other emergency nothing will be entirely lost.

As has been mentioned several times throughout this article, the Fort Lee Film Commission is woefully underfunded and deserves far more financial assistance than it gets. As an official offshoot of the Fort Lee Historical Society, the Commission gets an annual $10,000 budget from the borough, which is mainly utilized for restoration of items in the collection, acquisition of new items, and community education and outreach. Occasionally, the Commission applies for and receives grants for projects, such as producing a labeled map depicting the historic film-related sites in and around Fort Lee. Direct donations are also accepted – and encouraged. The Commission also spends money to acquire permits and the occasional film showing or full-blown festival, which usually requires additional fundraising on the part of the Commission. Fundraising for the Commission comes in many forms and ranges from sales on official books and merchandise to fundraising events, including a John Barrymore pub crawl through Fort Lee. (No one can accuse the Commission of not having a sense of humor.)

Perhaps the Commission’s favorite event to raise funds for, however, is the annual high school film festival it sponsors. The winning students often get scholarships and other awards, and the festival and the students’ work helps to foster interest in Fort Lee’s film history (and the potential future of film in New Jersey). More than a small amount of the Commission’s annual funds go into this film festival, so fundraising is even more important when one considers that the Commission is working towards the future of film, not just the past.

Money is, as one can imagine, the Fort Lee Film Commission’s biggest challenge at present and will likely continue to be a problem into the future as long as locals are unaware of the amazing state history around them in the greater Fort Lee area. Until locals understand New Jersey history more and are willing to help and preserve it, the Commission is going to have difficulty acquiring funding and support. Although $10,000 can pay for most of a semester of graduate school, to a museum, no matter how small, this is a meager amount of funding, especially an institution with limited resources that is frequently tasked with preserving one-of-a-kind films from being lost forever.

To solve this problem, the Commission often turns to applying for grants, hosting fundraising events, and increasing its community outreach as much as possible in order to obtain more funding and continue its restoration work and education initiatives. Education is a particularly important element of the Commission’s work, as it believes that the more locals are educated about their own history the more likely they will be to help and preserve it, and so a large amount of the Commission’s budget is allocated towards its education programs. This, of course, eliminates a large amount of money needed for other things, such as archival supplies and film restoration, and therefore the Commission dearly needs a larger budget from the town in order to bring its work to the next level.

Another problem the Commission faces is the lack of interest in filming in New Jersey. One of its major outreach programs involves trying to bring certain film industry elements back to New Jersey (which would create numerous local jobs and would increase positive publicity for the state). Mr. Meyers told me about Governor Cuomo’s incentive program for filming in the state of New York and how effective it is in bringing money back into the state, and he wishes to begin an initiative to do the same in New Jersey. However, with little understanding of the history of film in New Jersey and a generally negative view of the state in the public eye, this is a very difficult undertaking and is another wrench in the Commission’s gears.

I spent roughly an hour and a half talking to Mr. Meyers about the Commission and its holdings, and over that span of time (although briefly interrupted by an elderly museum visitor who didn’t seem to realize I was doing an interview of sorts) I learned a great deal about an organization that deserves far more attention, funding, and supplies than it receives. The Fort Lee Film Commission, though extremely small, is also extremely ambitious and plucky (not unlike one of its – and my – favorite historical figures, comedienne Mabel Normand), and it does its best with the resources it is allotted and has access to. The Commission’s collection is absolutely fantastic and is much larger than one would expect from a tiny organization with only one full-time paid employee, a fine representation of the dedication and love put into it by its small band of volunteers. Its efforts to preserve and in many cases restore films shot in Fort Lee during the 1910s and 1920s are also amazingly impressive despite the organization’s size – boasting the only copy in the world of Éclair’s 1912 Robin Hood is no small feat, and the Commission’s work in raising the required funding for the film’s preservation and restoration and its subsequent screenings of the film are examples of just how expert its employees are, regardless of whether or not they actually receive a paycheck for their hard work. The Commission, to most of its employees, is a labor of love, which endears the organization to me even more.

A large part of the collection is scattered around in the attic of the Fort Lee Museum, and although this seemed somewhat disorganized at first I found out that the Commission employees know exactly where every item is and have an organization system that makes sense to them and allows them to pull their resources out for inquiring researchers. As I explored the actual archive in the attic more, I realized that things were not disorganized at all and that the Commission just needed much more space than they currently had, a problem that will hopefully be solved upon their planned move to the film museum that should be complete within the next two to three years.

Overall, I walked away with a very favorable impression of the Fort Lee Film Commission. It was evident to me that despite their limited resources, funding, and space, Mr. Meyers and his employees work extremely hard and do their very best to preserve and restore the films, stills, props, and other historical artifacts and ephemera in their care. I sincerely hope that the organization receives the attention, funding, and museum that it truly deserves in the near future – and until they do, I’m going to start volunteering with them in January to help them scan the items in their collection to do my small part because every little bit helps.

And for the record, I’m now halfway done with my Master’s in library science (with a focus in archival studies). Yay! Halfway to getting my social life back!

BBC One Commissions a Laurel and Hardy Biopic, Steph Invests in Tissues

Biopics tend to be either really good or really bad. Either way, they usually make me cry for various reasons.

In 2007, when I first watched Not Only But Always, Channel 4’s 2004 film about Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, I cried a lot. Double acts have always made me emotional, and when you combine one of my favorite double acts ever with high-quality British television, you get a tearjerker.

The BBC’s going to make me cry a lot more in 2014 because they’ve got a biopic coming up about a double act with a really good relationship that tells a story from later in their lives about their friendship.

BBC One has commissioned Stan And Ollie, a biopic focused on the later years of Laurel and Hardy, the double act who became famous worldwide for their slapstick comedy films.

The 90-minute show, which is being overseen the corporation’s in-house comedy department, aims to tell the tale of the duo’s 1953 UK tour.

The one-off TV episode has been written by Jeff Pope, who recently worked on the movie Philomena, and prior to that the TV comedies The Security Men and The Fattest Man In Britain.

Stan Laurel was an Englishman, whilst Oliver Hardy was American. Laurel entered the world of theatre aged 16, and set sail for America a few years later on the same ship as Charlie Chaplin with the aim of appearing in films.

He forged a successful solo career in Hollywood, however after starring in the silent short film Putting Pants in 1927 with the heavyset Harlem-born Oliver Hardy, the duo soon became a double-act. As a team, they went on to perform in 107 films, including the likes of Big Business, and became an inspiration to generations of comics, including Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise.

Speaking about the new production, the BBC say: “It tells the story of the duo’s 1953 UK tour. Their shtick – Stan the wide-eyed ingénue, Ollie the pompous fool, their meticulously rehearsed physical routines and their charming musical numbers had made them superstars all over Europe, South America and beyond. However, a split from their controlling mentor, the vagaries of studio politics and a run of poorly received films had resulted in their star falling. A series of acrimonious divorces, alimony battles and Oliver Hardy’s failing health didn’t help.

“The British tour was supposed to relieve some of the gloom and, despite numerous glitches, the public loved them. Audiences grew and grew as word spread that Laurel and Hardy were back and as funny as ever and, as audiences swelled, so did morale. But as their careers and friendship blossomed, disaster struck as Ollie suffered a heart attack. He tried to carry on performing on the tour, but it became clear that he was too ill. Replacement performers were found to fill in but, without Stan and Ollie’s charm and warmth, the shows simply weren’t the same.

“Eventually, with it clear that Hardy’s health problems were serious, Stan was offered the chance to perform alone, but refused. He realised that neither worked without the other, that they were so much more together than they were apart. Appreciating the sacrifice made by his friend, Ollie roused himself from his sickbed for a few last, triumphant performances, the very last of their extraordinary career.

“Ollie died not long afterwards and Stan never performed again, but their films endure and are still popular all over the world half a century later.”

Charlotte Moore, the Controller of BBC One, says: “Stan And Ollie demonstrates the fabulous range of comedy on BBC One. Written by Jeff Pope, this is a poignant single film about one of Britain’s best loved double-acts.”

BBC Comedy Commissioner Shane Allen adds: “Stan And Ollie is Jeff’s love letter to two pioneers and enduring giants of screen comedy. It beautifully captures the deep emotional bond forged over a lifelong partnership as they reflect on their rollercoaster careers through the prism of this final UK farewell tour. An epic story about the world’s most famous comedy double-act to date, told with great insight and heart.”

The programme will be filmed and broadcast in 2014. Casting details are expected to be announced early next year.

This was, indeed, their last overseas tour, as Babe Hardy passed in 1957, just four years after they were abroad. By this point, both of them were aging and not in the best health, but they had also become extremely close after touring together and essentially being next-door neighbors since the 1940s. At this point in their career, they really were the best of friends, and that makes this even more emotional than it is already.

Basically, I’m ready to sit there and sob for 90 minutes.

The Adventures of Plushie Laurel and Hardy: Part 2

I’ve taken Stan and Babe more places now. You think a 24-year-old graduate student wouldn’t take plushies all sorts of places to pose them and whatnot, but I do. Quite a lot, actually.

For their previous adventures, you can read part 1 here.

The boys have become good friends with my cat (the famous Murphy). He likes sniffing their hair.

I take NJ Transit into the city for my commute to grad school…and now so do they. Sometimes.

Just to prove we were in Manhattan, here’s a commemorative photo.

One of my classmates who’s friends with me on Tumblr posed with the boys, too.

A few weeks later, I took the 6 train up to 96th to walk over to the Jewish Museum for the Chagall exhibit. My co-workers and I were headed over there for a work field trip because we work at a historic site that has some Chagall stained glass windows. Guess who came with me so they could see the Pelham 123 train.

That was followed up by me actually having class, so they were very tired by the end of the day. So, frankly, was I.

Sometimes they also come to work with me and keep me company when I get bored because nobody’s visiting. It’s nice to have pals around.

I’m also learning to sew properly so that I can eventually make them some friends, so we’ll see how that goes. It’s been an interesting learning process, but now that I’ve been taking sewing stuffed toys a little more seriously than I did on my previous attempts as an undergraduate I’m actually learning a thing or two about how it’s done, which means I’m improving slowly but steadily. Fingers crossed!